Documenting Code

Pages which include source code, either directly or linking to modules.

This tutorial is about using Sphinx for more than documentation. Sometimes, though, you want code -- inside your website. You can still do that when using Sphinx and Markdown, and the combination has both some treats and pitfalls. Let's take a look.

Code In A Document

It is quite common in Markdown to just embed a code snippet in a page. Markdown calls these "fenced code blocks" (or code fences, or code blocks) as they use a triple backtick enclosing symbol.

Sphinx has a concept of code-blocks. Thanks to MyST, we can combine these two and use Markdown code fences (triple backticks) to generate Sphinx code blocks:

```

def hello(name):

return f'Hello {name}'

```

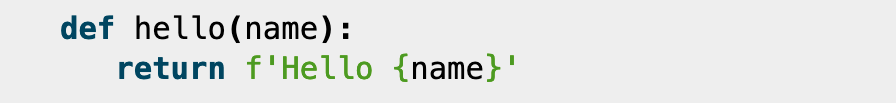

This renders with syntax highlighting:

Of course, you might want to tell Sphinx what language is the code block, to get the correct syntax highlighting.

Sphinx uses Pygments for syntax highlighting, with python3 is the default.

But perhaps you want to show a JavaScript snippet.

Just put the language after the first triple-backtick, from the list of languages supported by Pygments:

```javascript

function hello(msg) {return `Hello ${msg}`}

```

Sphinx has a number of options for code blocks. This requires, though, a more explicit MyST syntax that connects into code blocks:

```{code-block} javascript

function hello(msg) {

return `Hello ${msg}`

}

```

As mentioned in More Pages, this is a code fence, but with:

- Something in curly braces and...

- Something else after it.

The stuff in the curly braces maps directly to a Sphinx/reST directive. The stuff on the same line, but after the curly braces, is an argument to that directive.

You can show line numbers by passing options to the directive:

```{code-block} javascript

:linenos:

function hello(msg) {

return `Hello ${msg}`

}

```

Here is the YAML version of passing the arguments to the code-block directive:

```{code-block} javascript

---

linenos: true

---

function hello(msg) {

return `Hello ${msg}`

}

```

You can emphasize certain lines:

```{code-block} javascript

---

linenos: true

emphasize-lines: 2

---

function hello(msg) {

return `Hello ${msg}`

}

```

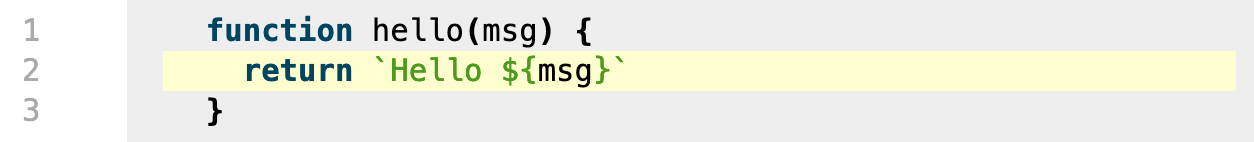

When rendered, you get a highlighted line and line numbers:

Sphinx code blocks have many useful options.

Including Code From a File

Inlining code snippets seems to be the dominant usage in Markdown. In Sphinx, though, it is more common to point your document at a file containing the code, then including the file's contents. Sphinx uses the literalinclude directive for this.

Thanks to MyST, we also have a Markdown-friendly syntax for this, similar to what we just saw.

Imagine we have a Python module my_demo.py in the same directory as a Markdown file.

class MyDemo:

""" A *great* demo """

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def hello(self):

""" Be friendly """

return f"Hello {self.name}"

We can directly include it, with syntax highlighting, using:

```{literalinclude} my_demo.py

```

Sphinx's literalinclude has a number of options, many overlapping with code-block.

Want to highlight two lines?

```{literalinclude} my_demo.py

:emphasize-lines: 2-3

```

You can also use MyST's YAML syntax for directive options instead of the RST-style of key-value pairs:

```{literalinclude} my_demo.py

---

emphasize-lines: 2-3

---

```

The literalinclude options in Sphinx are quite powerful and productive to use.

For example, you can use start-after and end-before to only include parts in between some matching text.

Configuring autodoc

Sure, this tutorial is about using Sphinx for websites, instead of docs. But the line between the two is thin. Perhaps you want a full-featured "knowledge base" website oriented around code. (Yep, me too.)

This brings up the centerpiece of the Sphinx ecosystem: autodoc. With Autodoc, you point a Sphinx doc at your code and it generates a structured, highlighted, interlinked collection of sections. Even better, the symbols in your code become "roles" in Sphinx which you can directly to.

Let us setup autodoc for use in a MyST-powered website.

First, in our conf.py, include the autodoc extension.

Also, add the current directory to the front of our PYTHONPATH, so our module can be imported.

import os

import sys

sys.path.insert(0, os.path.abspath("."))

extensions = [

"myst_parser",

"sphinx.ext.autodoc",

]

With this in place, you can use autodoc directives in your Sphinx pages.

Documenting a Module

Let's do that now.

We have a page at api.md into which we'd like to include some module documentation.

The Sphinx docs on autodoc show that this is straightforward.

For the MyST side, we need to use the escape hatch into reStructuredText directives, as explained in the MyST How To:

# About `MyDemo`

Let's take a look at this Python class.

```{eval-rst}

.. autoclass:: my_demo.MyDemo

:members:

```

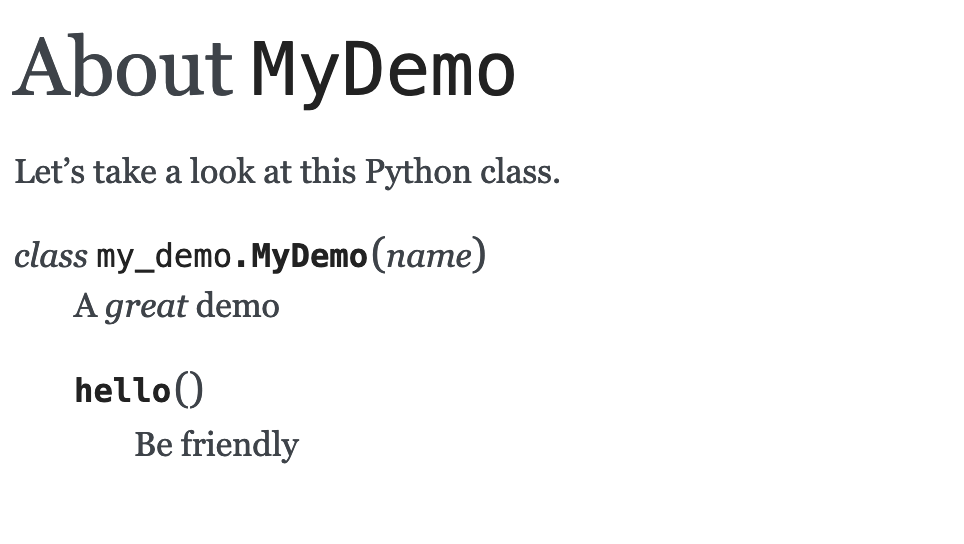

In this example, documentation for the MyDemo class will be inserted into the api page.

Here's what the rendered output looks like:

It's very rich output, with lots of links generated to imports, symbols, etc. We can actually do better, with richer formatting in docstrings and type hints.

Docstrings and Type Hints

Our my_demo.MyClass has a minimal docstring and does not use type hints for parameters and return values.

Let's change it to be a better-documented class:

class MyDemo:

""" A *great* demo """

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def hello(self, greeting: str) -> str:

""" The canonical hello world example.

A *longer* description with some **RST**.

Args:

name: The person to say hello to.

Returns:

str: The greeting

"""

return f"{greeting} {self.name}"

Python docstrings are reStructuredText, but don't have any conventions about the structure. For this, NumPy and Google have popular style guides for Python docstrings. For these, the Napolean extension (bundled with Sphinx) can support either.

The updated MyClass is using the Google docstring style.

It also uses Python 3.6+ type hints.

We now need to teach Sphinx to "interpret" these two new structures: formatted docstrings and type hints.

First, install autodoc extension package that teaches autodoc to handle type hints.

Add sphinx-autodoc-typehints to requirements.txt:

sphinx

livereload

myst-parser

sphinx-autodoc-typehints

Then install from the requirements:

pip install -r requirements.txt

Next, edit your conf.py file to enable both Sphinx extensions:

extensions = [

"sphinx.ext.autodoc",

"sphinx.ext.napoleon",

"sphinx_autodoc_typehints",

# And any other extension

]

Note: Make sure to load sphinx.ext.napoleon before sphinx_autodoc_typehints.

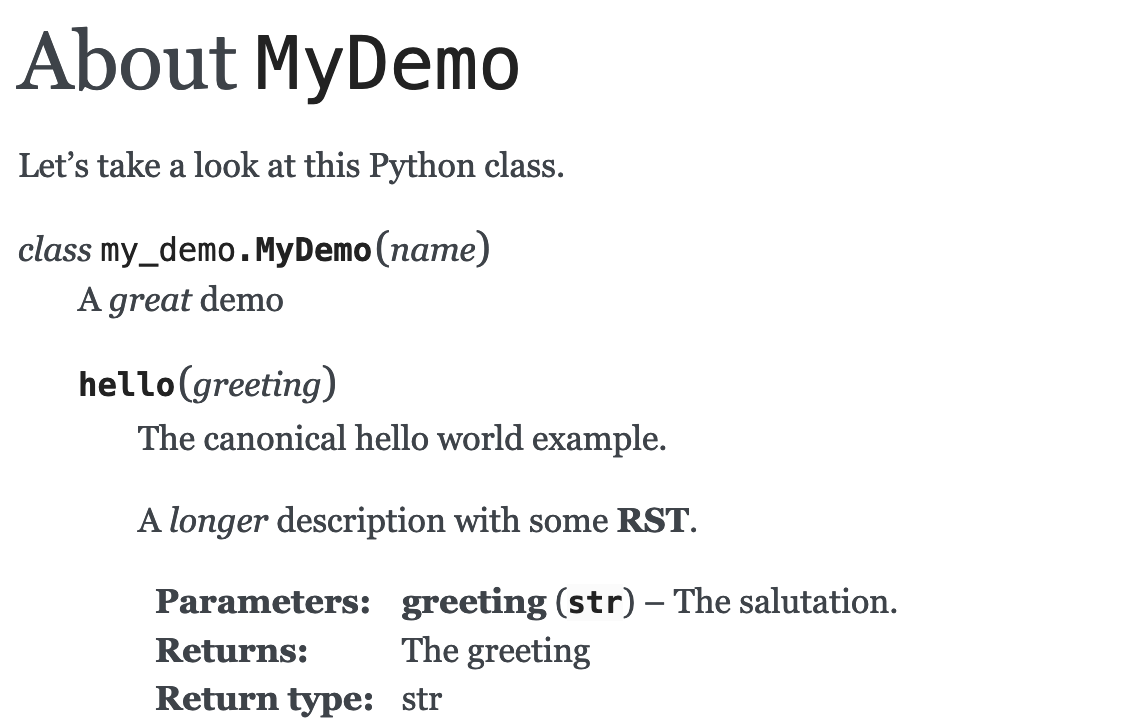

When Sphinx renders the next time, our page with the autodoc directive now shows nice docstrings and type hints:

It's visually attractive. More than that, though...it's semantically rich: links to navigate around, styling for the structure, and more.

More?

Referencing Symbols in Docs

As with other things in Sphinx, autodoc isn't just about getting pretty pixels on the page.

It's really about getting structure into Sphinx's "doctree".

With autodoc, the symbols in your code become roles that we can link to.

To see it in action, open about_us.md for editing.

In this page, we want to talk about MyClass and link to it, using Markdown-friendly syntax.

For example, we can use MyST "extended Markdown" syntax:

As we can see in [our Python class](my_demo.MyDemo), Python is fun!

This generates a paragraph with a link.

We can also use role-based syntax, with the Python domain as a prefix: This comes with an extra benefit, as link text is provided for you:

As we can see in {py:class}`my_demo.MyDemo`, Python is fun!

The link text comes from the target. Of course, we can also provide our own link text:

As we can see in {py:class}`HW <my_demo.MyDemo>`, Python is fun!

Conclusion

There are lots, lots more features regarding Sphinx and including source code:

- Directive options with fine-tuned control...after all, it is used for Python itself.

- Plugins which add extra features, such as the type hinting plugin.

- Importantly, central concepts that provide a lot of semantic structure.

If you have a website that is also about code, Sphinx and Markdown are a good choice.